A Drawing, Not a Picture

If nature takes its revenge but no one is around to witness it, will it be beautiful?

There is no SKYLINE this week as we are in production.

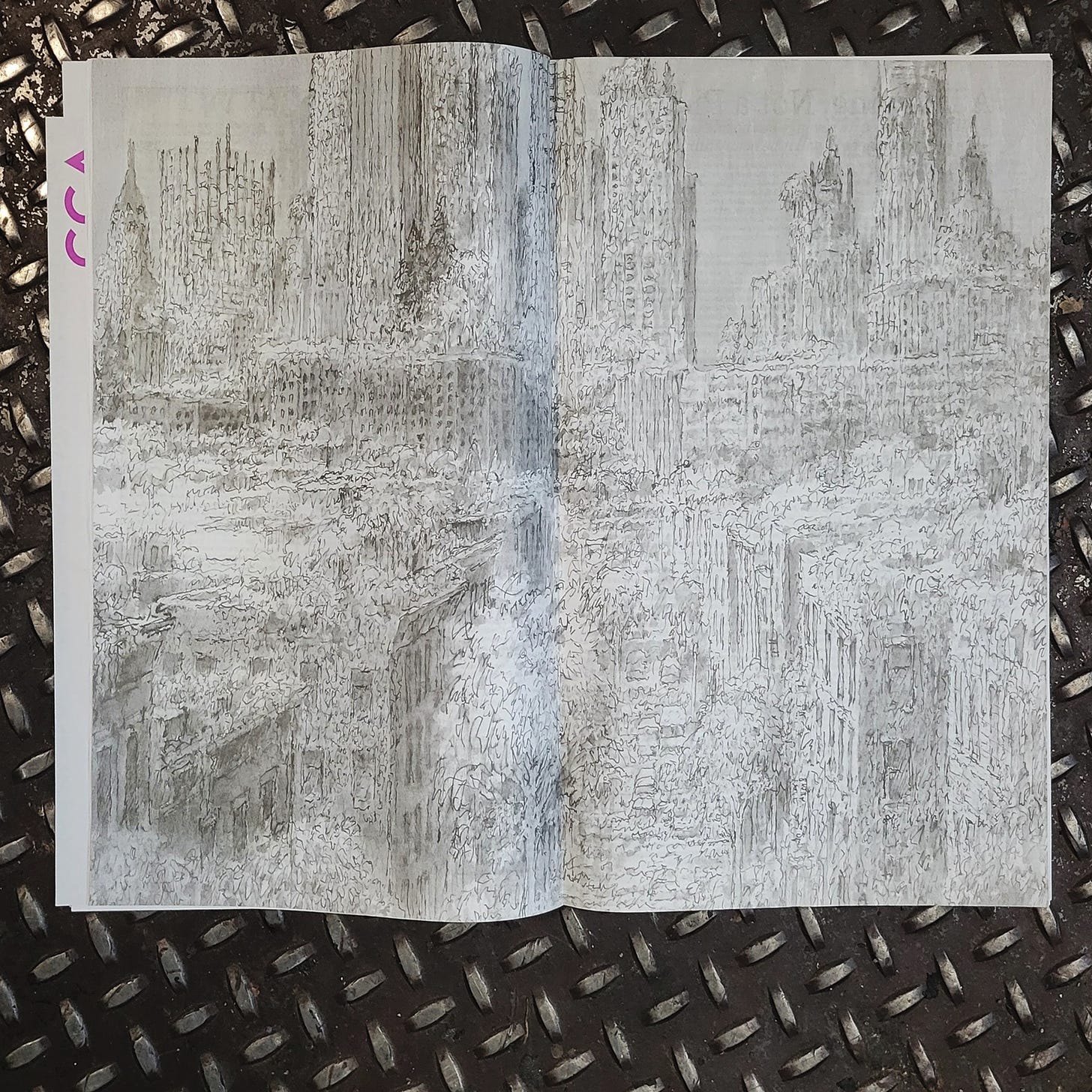

Since the beginning of New York Review of Architecture, back in 2019, each issue has featured a lively mix of drawings, collages, and even — on rare occasions — photographs. Our current issue, #33, features a special piece of art that both continues that commitment and marks the beginning of a new chapter for us. Its centerfold features Nature’s Revenge, a spectacular new drawing by James Wines, commissioned for our pages by NYRA Editions.

If you would like to see the drawing in person, you can subscribe before we launch our next issue and we will send you a copy of #33, or find the issue on our shop.

In January, Phillip Denny sat down with Wines to discuss the drawing. Read the full interview, on our website, or here below.

Born in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1932, James Wines founded the architecture and environmental arts studio SITE (Sculpture in the Environment) in New York City in 1970. The studio gained early notoriety for imaginative public spaces and mind-bending buildings, including the iconic BEST Products showrooms and boutiques for pathbreaking fashion designer Willi Smith. Today, Wines continues to direct the studio, which recently completed a series of shops for Off-White, the influential fashion brand founded by late designer Virgil Abloh. Drawing has been an essential facet of Wines’s long career, and his works are featured in the collections of major museums worldwide. In this conversation with Phillip Denny, Wines discusses his latest drawing series.

PHILLIP DENNY:

Tell us about this drawing, Nature’s Revenge. You said before that it’s the first in a new series of drawings showing at the Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago. What are you thinking about with this cycle?

JAMES WINES:

Actually, I found a drawing I did for the Pompidou Centre. They were going to do a big exhibition back in 2009 on the greening of Paris, so I made a poster for them. I forgot it completely. I recently wrote to the curator and I said, “Well, can you go through your archives and see if you could find it? Because I think I sent you the original, but I can’t remember.” It’s like the Pompidou Centre is sort of being consumed. It’s good, and it is a precedent for this new drawing.

PD: The city being overrun by foliage and greenery has been a theme in your drawings since at least 2009, but also much earlier, too—I’m thinking of the BEST “Forest” Building from 1980.

JW: It’s one of those things that you can keep interpreting forever. I wanted to do it just simply because, graphically, it would be interesting to have just something absolutely parched and something consumed by wind.

PD: Walk us through that process. How do you imagine a natural disaster, and how do you make it into something beautiful?

JW: Well, you draw. I’ve been doing it for so many years, I can just start with a pen. But I think it through. I had a lot of reference pictures of the Lower East Side, so I knew kind of where I was coming from. I use a Montblanc pen because they make a superfine line. So I do mark it out with a fine pen and organize what I want to do. Then I just start trying to figure out where my compositional points are going to be. I decide the dominant theme is vertical. I start with where light and shadow do the most good, what the nature of the drawing is. I mean, even carrying little structural things, and then doing this here because you get that and that. All those moments are building tension within the aesthetic thing, which some people understand but a lot of people don’t. They look at a drawing and just always see a picture.

PD: You work the drawing as you go. You make decisions as you’re sketching. Then, at the end, is that when you add this sort of wash, or watercolor?

JW: Well, the ink is water-soluble. So I just use brushes.

PD: Oh, really? So for instance, these darker areas are simply you going back in with a wet brush and smearing? The drawings are actually just ink on paper.

JW: Yeah. Back and forth, back and forth. Ink on paper. It’s something I evolved over a lot of years. It’s funny—in the Chicago show, they have a few of the very first drawings I made for SITE. They’re really crude. But I could see even at that time that this was going to go somewhere. And it did. The show goes in sequence. I didn’t get started with architecture until about 1969, and there are some drawings from then. But then the work goes around the gallery and you see it gets more and more and more.

PD: I wanted to ask you about those early days and your shift into architecture. Before you founded SITE, you were developing a career as a sculptor. You went to Rome as a fellow of the American Academy in 1957, you received a Guggenheim Fellowship a few years later, and then you were exhibiting your work in New York galleries. But around 1969, there’s a shift to a larger scale. Not just sculptures but environments, and maybe something like architecture. What guided that move from making objects to crafting spaces?

JW: I was a sculptor doing public art, the plunked-down sort of thing. I did these concrete and steel sculptures and fusing those materials together. It was technologically very difficult to do well. Architects liked it. It had an architectonic quality. I was doing big circular sculptures, which they liked because they went well with rectangular shapes. So my career was as a sculptor. I was at Marlborough Gallery. I was still early in my life. In fact, I went right out of school and into a gallery. I also worked with my father building homes in the summers. His sons always worked on them, so we all knew a lot about how to make buildings and put them together.

PD: So you were involved in building from a young age. You knew your way around a construction site. Did that familiarity with construction and blueprints influence your drawing practice?

JW: Well, I was drawing then but in a very different way. You have habits and idiosyncrasies that come out over time, but basically, it was just pen. I didn’t do washes. The drawings weren’t tonal. I didn’t get into the psychology of tonality until I lived in Italy. The thing that occurred to me there that was probably the most profound revelation is that buildings, public spaces, everything dealt with sunlight. Look at Borromini or Bernini. All that surface. They used sunlight masterfully. It’s about how light falls on the stone, the floor, the walls. It affected me profoundly.

PD: 1956 was pivotal—your year in Rome. You arrived as a sculptor, and then…

JW: When I got back, I had the idea of leaving sculpture, abandoning sculpture per se. I wanted to try to figure out what our language should be. At least [Bernini and Borromini] had all that symbolism and iconography to work with. Now we have practically nothing. After Italy, I kept trying to think how you could invest architecture with content other than shape-making and structure and functionality and whatever. That’s when I got started. Frederick Kiesler took a real liking to me. He just had that capacity to understand in depth what other people were doing and talk to them. And he never did it in a critical, formal way at all; he was always looking at the conversation. We were quite close in the last years of his life. He looked around my studio one day and said, “James, your work is heavily influenced by modernism and especially constructivism. But modernism and constructivism are pretty old-fashioned, and so is abstract art.” I began to listen to him. One day I just woke up and I looked around and I thought, “However skillful I am, I’m not really doing anything different.” It’s like that great statement by Duchamp—“In order to be creative in your life, you have to clean off your desk at least three times.” It’s so true.

PD: I just want to pull together a few threads in the conversation. It’s in Italy where you realize that form and space are nothing without light, especially at the architectural and urban scales. As you said, without light and shadow it’s just shape-making. That’s what you take away from Borromini and Bernini. To me, that recognition foreshadows everything that comes later because when you realize the primacy of light and shadow, it seems to me that you are really recognizing environment as a condition that you could work with creatively—whether as an artist or an architect.

JW: I was fascinated with minimalism when I started working on the first BEST showroom. The fact that the site was nothing. It was absolute banality. It was just commonplace subject matter. That was fascinating to me. I realized that if you can invest something with meaning just by doing it, then you can do anything. That’s how that whole series of showrooms got started. It was minimalism but with humor. I started doing what the architecture world said was forbidden. That was the mantra that controlled my life: “Humor has no place in architecture.”

PD: The brilliance and the controversy of early minimalism was the absolute literalism of form. It couldn’t be simpler. But inserting an object into an environment, producing a situation, was akin to setting a stage for something to happen. Much of your work has that theatrical quality, but especially the BEST showrooms.

JW: It’s a total send-up of that entire junk culture world. The Lewis family who did it were big collectors of Pop Art and were attuned to the idea that art could have other content, other values, other messages. I got more and more interested in the problem of our contemporary language, what it was supposed to be. I thought, “I don’t have church and state iconography anymore like Borromini had. So what do I have? Well, I have the context—wherever the thing is. What’s a site about? What exists in that context that has meaning, that has inherent content that you can bring into the architecture?”

PD: For you, architecture’s content is its site specificity. Your context could include a concept like junk culture. Can you say more about that?

JW: About once a day I get a request for a BEST showroom image, or a request for comment, or something related to those projects from the ’70s. For the media, an iconic work always becomes the only thing you ever did. Jasper Johns said it very well: “I’m the guy who painted the American flag, and that’s all I ever did.” I have a little bit of resentment toward the fact that, yes, the BEST series was a breakthrough, but that’s not the only thing that context means. Context means a lot of different things. It could be the topography. It could be the vegetation. It could be the way people move. I have to admit, the strength of the BEST buildings was what I call the psychology of situation. What people’s expectations were versus what they confronted. At the BEST showroom in Houston, there would be people standing in a big circle outside the building looking at it asking, “What does that mean?” It was a real success. But it also proved to me that there is content in architecture just as there is in certain visual art, movies, or whatever. Nothing’s worse than a movie that is just a showcase for good acting because that isn’t a movie. I feel a little bit of that about architecture. Yes, it’s form and structure and space—but what’s the content?

PD: It’s a bit like the difference between a great film and a great movie—a great movie is innovative but it is also entertaining. I think it’s harder to make a great movie than to make a great film.

JW: Oh, it is. It’s entertainment. You have that as one of the obligations. All art has that.

PD: And you would include architecture?

JW: Yeah. Everything has to have entertainment kind of as a foundation somewhere. It’s funny, I admire Donald Judd. I think anybody would have to admit that Judd’s first works, where he did the giant gray boxes that just displaced space so you began looking at the negative space rather than looking for sculptural values—that was genius. Then he started adding color, and the work looked like decoration by comparison. You can’t say that because he’s sort of a sacred icon in art. But that wasn’t anywhere near as thoughtful or as powerful as the idea of displacement.

PD: But maybe color is more entertaining. Judd’s work is iconic now in part because it was so controversial in its time. What was it like for you to do something different—controversial even—in architecture?

JW: Oh, my gosh. Well, it really grew out of an environmental art course I was teaching at NYU. The class and I started talking and began to ask, “Well, why don’t we get involved more with architecture?” A few of the students really got into it and we formed SITE together. The students did the first two blueprints for the Houston BEST Products showroom in 1974. We worked with Josh Weinstein, a consummate architect. He was so technical that he could listen on the phone to a contractor and could tell whether they were doing something right or wrong. He was one of the best. So we worked very well together because he had all the architecture skills, plus the qualifications, and was registered in about five states. One thing led to another.

PD: I’m curious about the architecture scene at the time. There were so many interesting practices emerging in that moment—both architectural and not, and running the gamut from radical to archconservative. Your friend Vito Acconci made Seedbed, his infamous ramp installation in the Sonnabend Gallery, in 1972.

But in architecture, you had “The New York Five” and this artificial rivalry between the “Whites” and the “Grays.” What was it like jumping into that scene? Who were your supporters, and who were your enemies?

JW: I would say 90 percent of SITE’s reputation happened abroad. In fact, the first article ever written about SITE was published in France, and the second one was in Italy, and then everywhere. Bruno Zevi was a great modern scholar who really liked our work. I could never figure out why because that wasn’t what he typically wrote about. He said, “What you do is really American. It’s not based on European design. It’s peculiarly American.”

PD: What did he find so American about you or about your work? What’s the Americanness?

JW: Junk culture, I guess. The asphalt world. SITE’s Ghost Parking Lot was repeated in twenty or so different formats. We recognized that the asphalt world and the automobile were so iconic that they were subliminal.

PD: Taking junk culture seriously would mean seeing the parking lot as an important public space. I can imagine the modernist architects would find that scandalous.

JW: Exactly. But it’s so iconic it can’t be ignored. Vito Acconci and I were such great friends. He said to me, literally on his deathbed, “You know, James, we’ve spent our whole lives defending artists to architects and architects to artists.” That’s true. We were always in the middle, trying to defend both camps. But the thing I think offended architects the most is that I’m an artist, not an architect. What right do I have to invade their territory? I wrote about architecture, but I always considered my own position as an artist, a visual artist, an environmental artist, really.

PD: You’ve been told that what you’re doing isn’t real architecture. It has taken a long time for the culture to catch up. Architects didn’t understand the value of bridging between art and the building. As you said, the work was seen as coming from the wrong place, thinking about the wrong things.

JW: That’s been my whole life. It’s really weird because, as I constantly rationalize it, my most fundamental revelation came from Italy. We did the last stores for Virgil Abloh in Asia before he died. He said, too, that the Italy experience blew his mind when he finally got to visit. He said it just changes your life. And it really does. It gave me the insight that there’s a thing called content. Say a painter just talked about how he was framing the pictures and how he stretched the canvas. You don’t want to hear only that. Architects always talk about service, or serving the public. It’s fine. It’s good. It’s very positive. But why is that the only thing they talk about? It’s part of it, but not the main thing.

PD: Fellow artists accepted and understood your work in a way that architects wouldn’t. I know Louise Nevelson was also a supporter of yours, a kindred spirit.

JW: Oh, Louise. My studio was very near hers and she really liked me. That was when I was doing sculpture. She was really one of the first environmental sculptors. She had this house that was full of her work. She built the works right into the wall, which was spectacular. She was an amazing woman, one of my really dear friends and a majestic woman. She had a presence, very tall, Russian, with a Russian accent. She was not the kind of person who made small talk. She was constantly hosting visitors in her home. The Museum of Modern Art would send twenty women from Westchester or somewhere. On one of those days, she calls me, “Oh, James, do you want to stop by? I don’t want to explain the work. Will you take over for me?” I did it about five times. I would come to the house, be the guide, and explain the work a bit. Halfway through, Louise would try to stand there and be polite and gracious and give them all drinks. Once, this little woman from Westchester came rushing up to her and just broke through the whole room and said, “This is not art. I have this little nephew named Fergie, and Fergie could do this. He’s a carpenter. He could do this.” And Louise, very stern, says, “Let the little fucker try.” Total silence. Everybody whispered after that. Tiptoed around.

PD: An absolutely perfect response.

JW: It’s the kind of thing you always wanted to say but didn’t have the courage.⬤

Support the work and see the drawing in person: you can subscribe and we will send you a copy of the issue (while it is still our current issue), or find the issue on our shop.