Hands predominate in the earliest projection works of the Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko. Scotia Tower, his 1981 intervention in downtown Halifax, Canada featured a single hand (left) with thumb and fingers pointed decisively downward, like the hand of a soldier standing at attention. The disembodied hand was enormous, some twenty feet tall. It had been beamed onto the blank side of a midcentury concrete office block from a nearby rooftop. Wodiczko’s phantasmic hand transformed the spartan, sober structure into something altogether more human and vulnerable: a gawky giant. In an interview last year, the artist admitted that this simple intervention was the beginning of a long journey and the first of many projections, though he couldn’t have known so at the time.

If Wodiczko had an inkling that the technique held promise, his suspicions were confirmed by the public’s reaction in Halifax. Not long after the projector was switched on, he heard a chorus of laughter on the street. “They were just laughing loudly, and I realized that there’s something,” he said, “because when people laugh they don’t know exactly why they laugh.” They were bemused, perhaps, by what Wodiczko calls the “architecturization of bodies and the bodification of architecture.” Rendering buildings literally anthropomorphic, he realized, could shed light not only on the constructedness of our environment, but also on its strictures and shortcomings.

Subsequent projections took on a more overtly political bent. Wodiczko’s 1983 work Hauptbahnhof, in Stuttgart, Germany, added a pair of clasped, suit-cuffed and manicured hands onto the clocktower of the Paul Bonatz-designed central train station. Appearing below the tower’s permanent architectural features — an illuminated clock face and a monumental, rotating Mercedes-Benz logo — the artist’s intervention was an anarchic détournement. The projection reprogrammed these familiar icons of civic life and industrial prosperity as elements of a commentary on the city’s long-standing class divides, the persistent social gulf that separates white-collar workers from immigrant laborers.

In the United States, where Wodiczko has lived and worked since 1983, the projections brushed against the grain of their broader political context, taking public space as “both a target and a weapon,” as the art critic and historian Hal Foster observed. In 1988, the artist mounted a projection on the curved exterior of the Hirshhorn Museum on the National Mall in Washington just one week before the presidential election. (That work was restaged in 2018.) The projection took its cue from George H.W. Bush’s infamous “thousand points of light” speech at the Republican National Convention, and featured a pair of hands, one holding a candle and the other, a polished revolver aimed menacingly outward. A row of microphones stands in the middle of the image, with the cyclopean balcony of the Gordon Bunshaft-designed museum hovering overhead like an open, unspeaking mouth. For Wodiczko, the work dramatized the patent contradictions of a candidate who was at once both “pro-life and pro-death,” opposed to abortion rights and in favor of the death penalty.

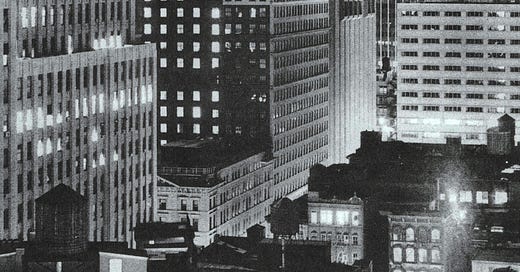

The work shown here was executed in 1984, just a few days prior to the election that gave President Ronald Reagan a second term. In this case, the hand is not anonymous, nor is the gesture ambiguous, as in earlier works. This is the president’s hand swearing the Pledge of Allegiance. Here, Wodiczko has laid claim to a blank façade of the John Carl Warnecke-designed AT&T Long Lines Building in Lower Manhattan, a 550-foot tall, windowless skyscraper whose sides are each a granite cliff face, among the tallest in the world. Several years ago, the building was revealed as the likely location of an NSA surveillance hub (codename: TITANPOINTE), but in the mid-1980s it resonated as an unyielding icon of corporate might. Wodiczko’s work is coolly indicting, revealing the complicity of forms of power — corporations and state — by rendering their superimposition spectacularly visible. Captured in striking photographs like this one, these transient interventions remain memorable long after the projections have faded from view.

PHILLIP DENNY is a writer and historian of architecture. He currently teaches at Pratt Institute and Princeton University. He is a PhD Candidate at Harvard University.

—

This piece comes from our current issue, #23. Subscribe to NYRA to receive a printed copy of the issue, which includes a full-spread risograph-printed poster of the work: nyra.nyc/subscribe

Image: Krzysztof Wodiczko, AT&T Long Lines Building, New York, 1984. Courtesy Krzysztof Wodiczko and Galerie Lelong New York.