by Ian Volner

The following article will be published in our June/July 2022 issue, #30. As it happens, the exhibition under review ends its run a few days before the issue’s release. So we decided to publish the text in full, both below and on our website. To support our work and receive #30, please consider a subscription.

Speed, beauty, and violence were Claude Parent’s birthright. His father was an aeronautical engineer in the early years of French aviation and his mother owned a furniture shop; born in Neuilly-Sur-Seine in 1923, he came of age during the Nazi invasion and occupation. His career as an artist-architect was defined by a kind of slashing, insouciant militancy: a self-drawn cartoon from late in his life features himself, brushy mustache and all, kitted out in medieval armor, skewering an opponent’s proposal with a lance. Of his approach (learned in part while apprenticed to Le Corbusier in the early 1950s) Parent is reported to have said, “One must arm oneself to defend every point.… The slightest detail can suggest you haven’t sufficiently thought through your ideas.”

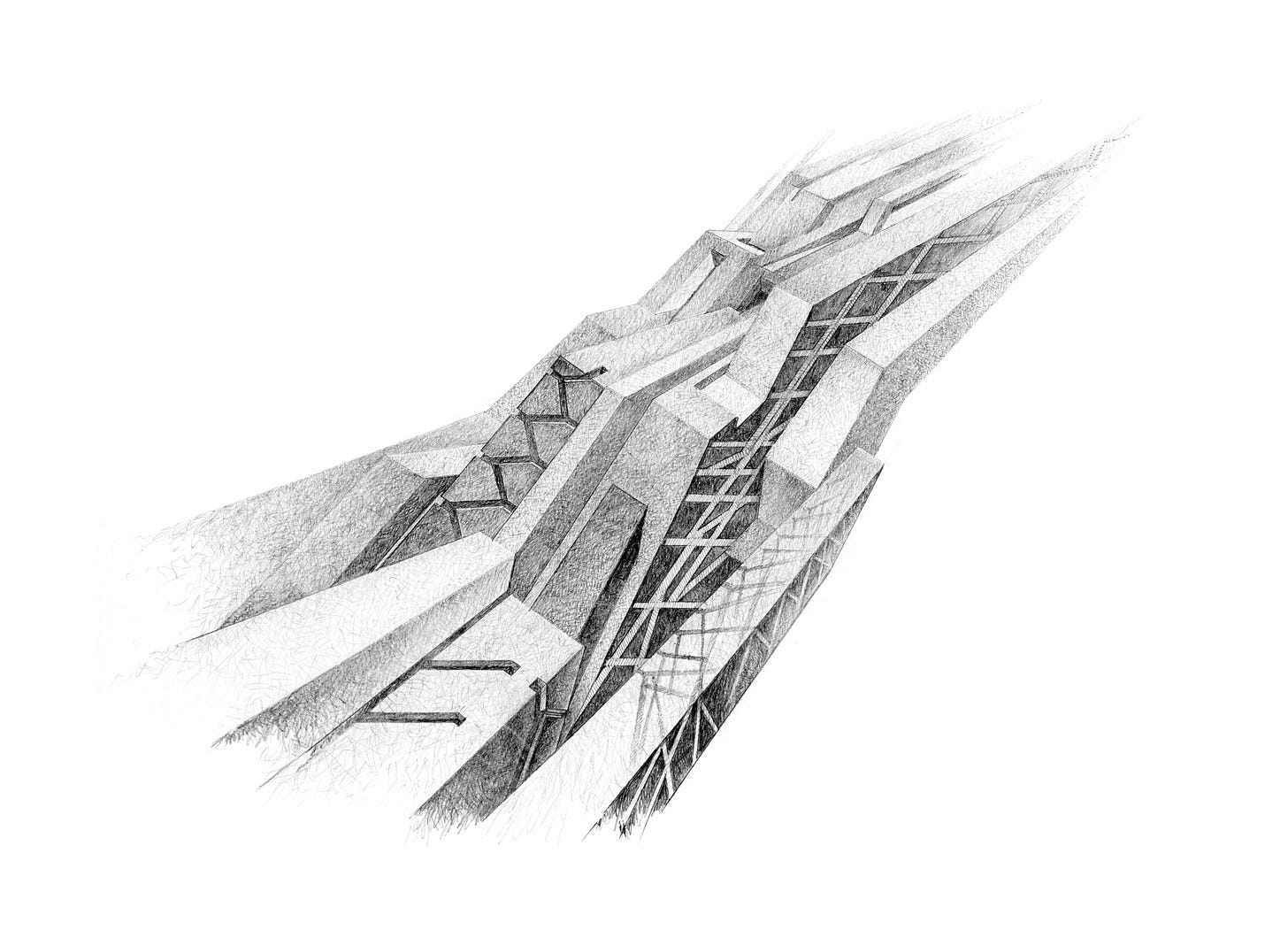

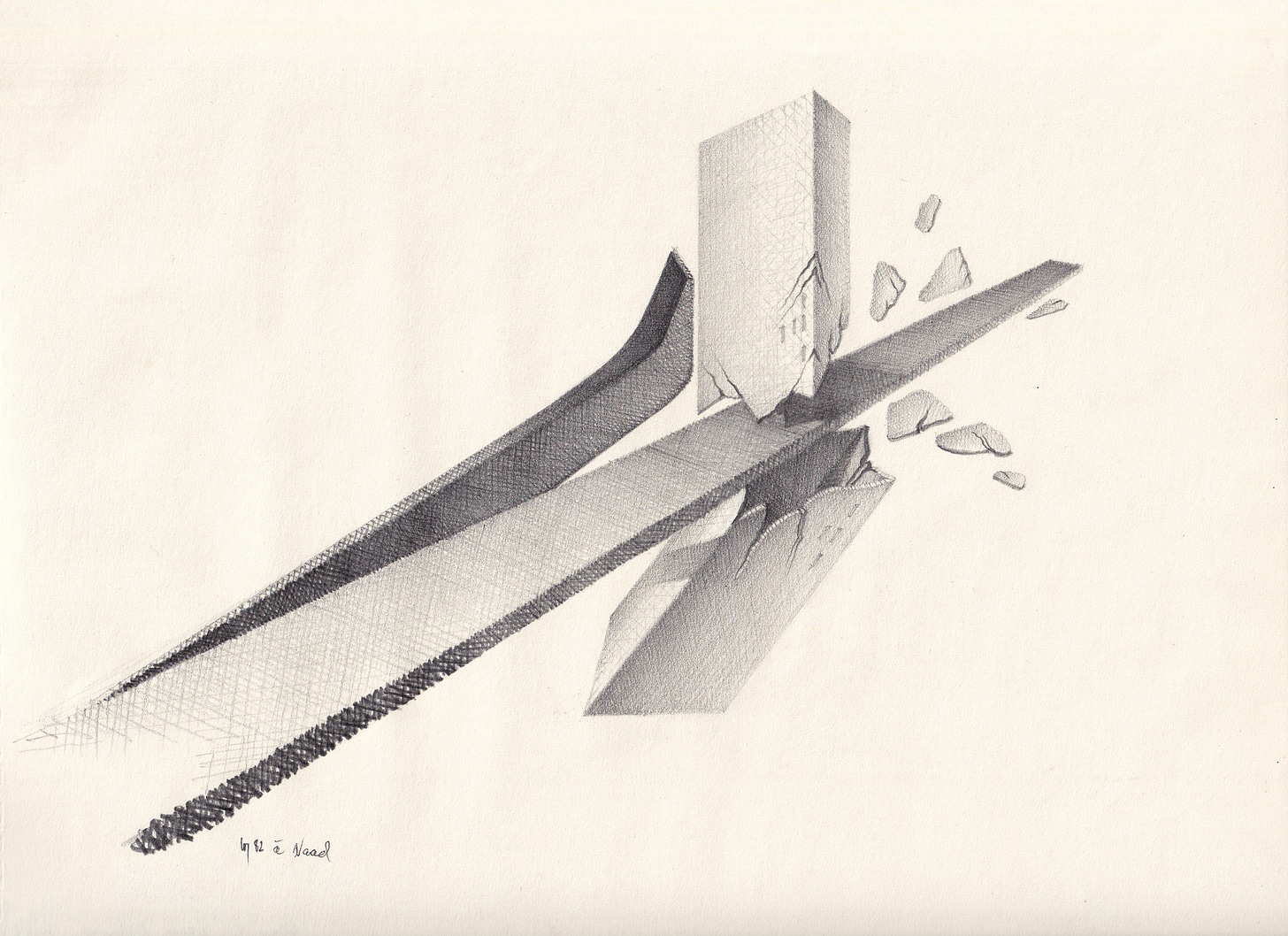

The architect’s rigorous devotion to an elegantly manic formalism is currently on full display at Soho architecture gallery a83, where the exhibition Claude Parent: Oblique Narratives No. 1 features 44 of its subjects’ hand-drawn renderings of imaginary fragments and facades, most of them from the 1980s onwards. A persuasive case for Parent as one of the foremost draftsmen of late modernism, Oblique Narratives will be followed next year by another a83 show examining his built work, marking the largest sustained effort to date to give the Frenchman his stateside due.

If Parent seems (and has seemed, even well before his death six years ago) a bit sub-radar, that’s more or less how he liked to fly. Abandoning his studies at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris just after the war, he chose early on to set his jaw against the architectural mainstream, teaming up with likeminded fellows including designer Ionel Schein and sculptor André Bloc in a bid to bust up the plodding, gridiron sameness of the emerging twentieth-century city. The breakthrough came with his introduction, in the early 1960s, to theorist and historian Paul Virilio, with whom Parent established a short-lived yet immensely consequential partnership. Drawing on Virilio’s studies of disused military bunkers, the duo created a small body of built projects—including the celebrated church of Saint Bernadette du Banlay at Nevers, completed in 1966—and a larger body of ideas—through their shared organ Architecture principe—that would exert a powerful influence, not just on Parent’s subsequent commercial and institutional work but on the whole profession. Challenging, wrought, spatially warped, the Virilian conception of a “cryptic architecture” to which Parent was so committed went on to become a lodestar for a generation of architects who followed.

Connecting the dots between Parent and subsequent development isn’t hard to do—Rem Koolhaas, Bernard Tschumi, and Daniel Libeskind have all written about and on behalf of Parent, while Jean Nouvel worked in the Virilio-Parent office—and it becomes even easier in sifting through the drawings on view at a83’s loft space. The exhibition (made possible by the architect’s estate) presents a shrunk-down version of the Parent archive through a giant filing cabinet with pull-out drawers and featured pieces set up on a central pitched easel. Right away, the material puts the viewer in mind of the work of Parent’s admirers: a pair of flowing, shoelace-ish volumes from 1982 seems like a presentiment of Zaha Hadid’s Sheikh Zayed Bridge from 2010; a futurist-Gothic shaft, all crisscrosses and jagged edges, anticipates Nouvel’s 53 W. 53rd St. high-rise in Manhattan. All of the drawings, really, look like surprisingly plausible architecture, the slopes and slides and geometric piles ready to leap from the shadowy cross-hatching of the graphite and into a high-rent apartment tower near you.

Which, of course, might be another reason that the aptly named Parent has seemed less visible with the passage of time—upstaged by his glittering progeny, the architect and his imaginings have receded somewhat into the background. But fancy technics and big money have also obscured the radical implications of Parent’s imagined fonction oblique. Of his signature theory, Parent once said, “For nine thousand years you’ve been living on horizontal planes and you’ve never considered an alternative”; what, he asked, would it “be like if space were understood more playfully, more freely?” Through the banishment of the static and the rectilinear, the architect believed that buildings could gesture towards a possible world, become engines for a new way of thinking and living.

Such a conviction is not generally leant much credence nowadays, having about it the whiff of a much-discredited proposition which even Parent’s most dedicated followers would be hesitant to embrace outright: that architecture, that sad little pimple on the rump of capital and the construction trades, can reach deep into its formal bag of tricks and retrieve some special critical agency and intellectual content all its own. Indeed, this proposition—known in some quarters as autonomy—is in such poor odor at the moment that it almost seems like a dare, on a83’s part, to mount not one but two shows about such an outspoken adherent of that particular view.

Then again, depending on one’s outlook, that’s exactly the charm of Oblique Narratives. The tough-minded seriousness, along with the inspired lunacy, of Parent’s aesthetic explorations is enough to make a gallerygoer fairly wistful, and maybe to reawaken a dormant feeling that perhaps—without embracing the heavy-breathing maximalism of, say, Peter Eisenman—architecture does have the very power Eisenman always insisted it has: the power to “speak of its own sacred realms.” As contemporary discourse looks determinedly the other way, we may be approaching the point the psychologists call ironic rebound, where the vaulting autonomy of Parent becomes the white bear we cannot not think about. In the end, we may find ourselves forced to consider once again whether there is, after all, a ghost in the machine for living.

Ian Volner has contributed articles on architecture, design, and home invasion to The Wall Street Journal, Harper’s, Penthouse Forum, and The Nassau County Hometown Shopper among other publications, and is a regular nuisance to Architect Magazine. He is the pauper of numerous books and monographs, including his latest, a calamity.

All images courtesy the Claude Parent Archives.

This article will be published in the June/July 2022 Issue of New York Review of Architecture, #30. Subscribe today to receive your copy.