Published April 6, 2020, in No. 10

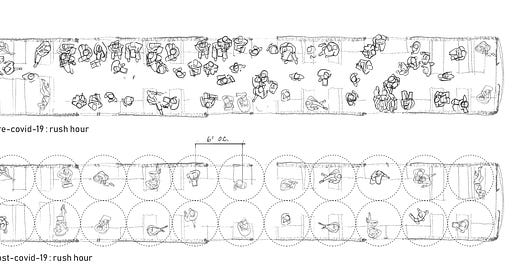

A pandemic is upon us, and we’ve entered a new epoch of six feet on center spacing.

Measuring our interpersonal distance is nothing new. In 1963, cultural anthropologist Edward T. Hall attempted to understand the experience of distance through his theory of proxemics, the “study of man’s perception and use of space.” As an ex-Foreign Service officer, he believed there was no singular experience of space and that “what crowds one people does not necessarily crowd another.” Therefore, there can be no universal index of social distances. He found that we all inhabit our own subjective worlds, which are shaped by how we interpret space and distance through cultural, visual, auditory, and olfactory inputs.

Hall developed metrics related to human comfort for middle-class Americans in relation to other people: intimate distance at one foot or less, personal at one-to-four feet, social-consultive at four-to-seven feet, and public distance at ten feet or more. With today’s six-foot social distancing requirement, the social-consultive distance is compulsory. A range meant for impersonal interaction in small groups, the mandates of social distancing restructure how we interpret the measure of space. With spheres of comfortable distances expanding, a new standard may emerge. It is possible that a reactionary movement of intimacy will follow, but will we grow to appreciate this extra space we’ve been given? Will cities be forced to build ever-horizontally to provide people the space they crave? Are we bound to sprawl more boundlessly than before? .

Our social perception is forcibly skewed as we all re-evaluate how much space we actually take up. Will we continue to populate cities that are overcrowded, having already caused emotional, financial, and mental distress? Densities are shifting, and it may be for the better.