SKYLINE | Time, Colonial Construct

It’s just one of many. Plus: A professor of meme studies schools the kids and Art Deco posters

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing to NYRA in print.

Welcome back to NYRA’s regular helping of news and views bubbling up from the city’s architecture scene and beyond.

NOTES & QUOTES

A Singular Devotion

CHELSEA — “I assume you all know the history of Art Deco,” Angelina Lippert, the magnetic chief curator of Poster House, told members from the Art Deco Society of New York as they gathered into the museum’s new exhibit. And while the large crowd of deco devotees nodded sagely—of course they did—it soon became obvious that our tour guide believed that probably we knew the history of everything, and only ever needed to be reminded.

“When we think of Art Deco posters, we think of Cassandre,” she said next to the French graphic designer’s famous bicycle advertisement. Several posters later, she noticed that maybe we didn’t actually think of anyone and perked up.

“For anyone who actually doesn’t know who Cassandre is—does anyone have a Yves Saint Laurent bag on them?” Someone did. “Can you raise it up? See, the YSL stamp? Cassandre did that.”

Lippert’s thesis is that Art Deco is the first global cultural movement, and that posters largely helped move it around the world, since they’re lighter than, say, a building. That someone in the crowd was unknowingly wearing the show’s star seemed to confirm this hunch. But what I have noticed about people who love Art Deco is that they are, in some way or another, always dressed like the Chrysler Building. I spotted bold metal jewelry and Nikes with a silver bar down the sole. The group’s enthusiasm was only exceeded by Lippert and her overwhelming knowledge, and indeed love, of her subject.

“This is all I do,” she told me after the tour. “I have no husband, I have no cat, I have posters.” —Lily Puckett

Meme Studies

UNION, NEW JERSEY — “I know Architectural Record says I am the godfather of memes, but they are nothing new—the internet just had a new way of understanding them,” said self-described “architectural influencer” Ryan Scavnicky during a talk at the Kean School of Public Architecture. After a preamble about the pre-internet history of architectural media (in which “the horrible Leon Krier” featured), he parsed memetic scholar Limor Shifman’s definition of the form (“a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance which were created with awareness of each other and were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users”) before setting off on a rapid-fire tour of his own ample meme production. Scavnicky is rumored to be the original mentor for the anonymous mods of the Instagram architecture meme account Dank Lloyd Wright (102k followers) and is himself the very not-anonymous author of sssscavvvv (16.2k followers), where now the architecture dunks share the grid with photos of his newborn. (“You make memes then you have a baby and everything changes and you just make presentations about memes,” he said of his transition from godfather status to fatherhood.) He had saved the memes for last, but the same punchy humor and efficiency of communication ran through the whole talk, which covered the work of his practice, Extra Office, and teaching, such as an architecture studio themed around Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas: “Rather than having [students] look at some building in France they could never go to, I [had] them draw the buildings they are constantly running through in video games.” Pin-ups were staged on Twitch, with those in the chat acting as the jury. If, as he claimed, memes thrive on the bits of arcana that form the boundary between in-groups and out-groups, his audience was clearly among the former. When a student project that involved a dancing avatar appeared on the projector, the crowd lost it. “Omg, are we laughing at this? Okay!” said Scavnicky, surprised and clearly delighted. —Nicolas Kemper

Unstable Ground

GOWANUS — Inside the Van Alen Institute’s Brooklyn storefront, the tenor of a community conversation belied the celebrations outside. As part of the institute’s annual block party, members of Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice (GNCJ) and an interested mix of public housing residents and built environment professionals had gathered to discuss the consequences of a rezoning plan approved by the City Council in 2021, which swiftly led to a glut of luxury housing development in the area. “The weight of these buildings is on unstable ground,” cautioned one participant. It was a reminder few in attendance needed: the previous day’s historic deluge hit Gowanus especially hard, where entire streets disappeared underwater; indeed, the skies cleared just minutes before the event’s start. Artists Juanli Carrión and Rodolfo Kusulas’s installation With Your Voice appeared to have been hurriedly installed along a blocked-off stretch of Bond Street. Resembling both megaphones and cartoon ninja turtles, the objects purport to amplify the voices of locals who would prefer an alternative future than the pricey high-rises topping out across the neighborhood. But the inclusion of QR code-summoned “gowanimals”—accessible at the artwork’s several sites—landed like an inharmonious improvisation. Back inside, GNCJ member and recent David Prize recipient Karen Blondel provided insight pointed to planning professionals at the urging of moderator Lynn Neuman. “We can’t offload our environmental justice problems,” Blondel noted of a plan included in the rezoning that would send ten times the area’s current sewer overflow to Red Hook. “It’s another part of redlining if you ask me.” Left unstated was Van Alen’s own somewhat awkward position in all this; the non-profit organization (it was formerly the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects) is among Gowanus’s more recent transplants, after selling its West 22nd Street building in 2018. Should the institute prove instrumental in putting the community’s health before the unsustainable growth in its proximity, then Gowanus residents will have reason to party for years to come. —Peter Walhout

Lie of the Land

MORNINGSIDE HEIGHTS — Academic talks, like the pair recently staged at the Buell Center’s under the name, Made Land, can be impossible to summarize—not because I find them confusing, but because every word is so carefully chosen. Like boulders being dragged into formation, the words plot, land, and reclamation were prodded throughout the presentations even while they served as chapter titles and thematic anchors. Word agonizing is what makes these people historians, honey, and that nitpicking attention is what brings alive the conditioning systems of colonialism and neoliberalism under which we all live.

My respect for discerning historians is also my excuse for saturating my summary with quotes. The event, which was part of the Buell’s ongoing Conversations on Architecture and Land in and out of the Americas series, brought together two scholars to speak about land that “has been ‘made’ from its edges inward” over the past four centuries (in other words, for the duration of capitalism). Deepa Ramaswamy of the University of Houston and Amiel Bizé of Cornell University shared research that the website description ever so carefully characterized as “showing how wealth is made from (and on) the edges of landed territories… Countering classical economics’ characterization that land’s value comes only from investing in the earth’s agricultural productivity, both speakers examine the long-term effects of alternate liquidities onto land’s shape and settlement.”

Ramaswamy showed maps and photos from Mumbai and Bombay, where the edge of both cities was expanded by “reclaiming” land from the sea, and how edges were defined by their uses as ports. The access and conditions of the coast have changed as it fell in and out of the hands of trading space.

Bizé talked about capital-P Plots in western Kenya, just outside the city of Nakuru. A plot as a unit of measurement is slippery to define as it fluctuates in proximity to city limits and the delineating highway; linguistically, it’s used in place of the word shamba, which means land/farm. Bizé related how “farming land [thus] turns to real estate land—indicating not only a division of area but a rupture of a set of ideas and land use practices.”

In a coda to the talks, Reinhold Martin of Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, said the talks helped us consider what “made land” is. Or as he exactingly put it, “How might this regime called land be made different (speaking in passive voice) and in active voice, how to can we name the makers and hold them to account in the remaking?” —Angie Door

Forceful Truths

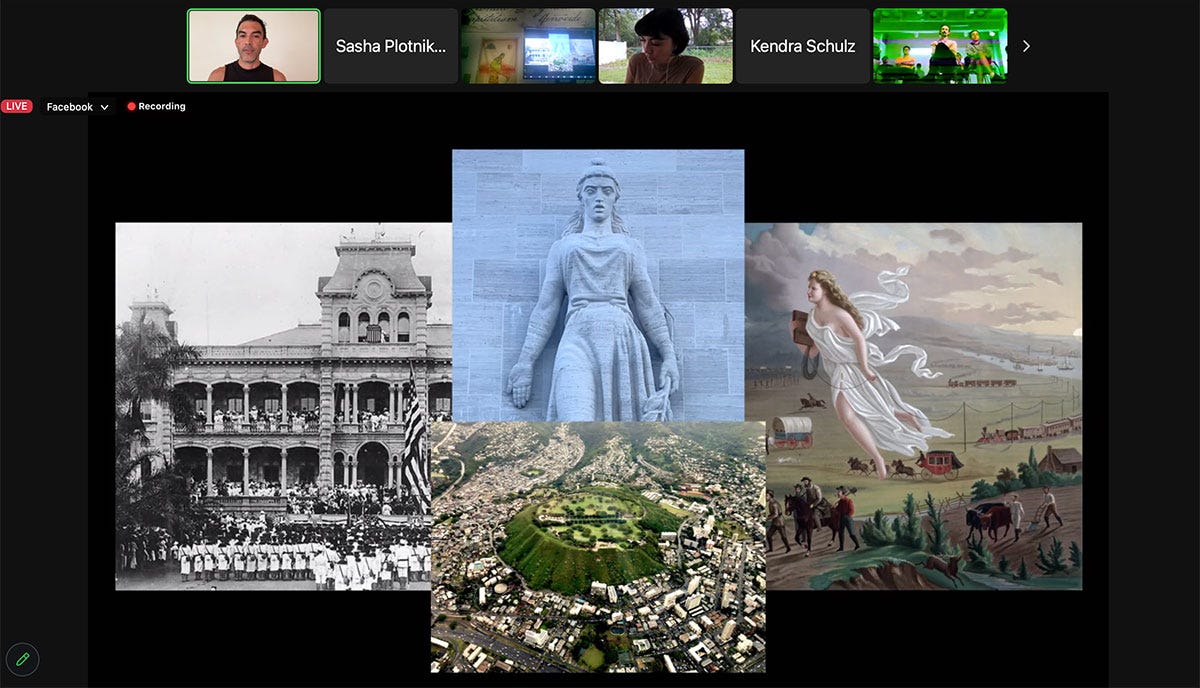

AMES, IOWA — A half-hour after logging on for the kickoff of From Land Grab to LandBack and seeing nothing but a black screen, the online audience saw an apologetic Cruz Garcia suddenly appear in the Zoom room. “Time is a colonial construct, and we are always punished by it,” Garcia, an associate professor at Iowa State University’s (ISU) architecture school, said, before turning the camera onto the Meskwaki artist Shelley Buffalo just as she was wrapping up her talk in the building’s atrium. “Obviously, capitalism must die,” we heard her say in closing.

So began the six-day-long conversation series, throughout which fourteen speakers proposed counter-narratives of different communities that have been subject to colonialism, sketching out their untold and under-documented histories. The artist Sean Connelly and architect Marakiani Olivieri spoke about struggles for demilitarization in Hawai’i and Puerto Rico, respectively. Ukrainian filmmaker Oleksiy Radynski shed light on the genocides and ecocides committed by Russia in Ukraine and northeast Eurasia in ramping up fossil fuel production. Buffalo presented on Indigenous aesthetic movements, prompting the audience to imagine how they might have developed had they not been interrupted by imperialist oppression. The writer Abu Salma Khalil simply affirmed his Palestinian identity as he joined us from France, a country whose government classifies him as “stateless.”

Speakers furnished a range of visual media—photography, digital models, Google Street View captures, even blood tests—in their presentations. Brazilian architect Gabriela Leandro gave a layered history of sites of colonization and indigenous resistance in the state of Espírito Santo by juxtaposing images from her own family history and indigenous music over video images of maps, landscapes, and urban environments. She pointed out that this mixed media approach allows her to “re-enchant” and “re-occupy” stolen lands within the narrative she read to us, and to depict her country’s violent colonial past without centering violence itself. Some speakers offered pathways to decolonization, though these varied in scope. Connelly, for example, proposed a “land back urbanism” that identifies areas containing resources key to sustenance and prioritizes their return to Indigenous stewardship. The Caribbean artist Nadia Huggins demonstrated how to look differently by way of her underwater photography, which subverts the tourist gaze by protagonizing not the beach but the sea, with all the marine and human life that flourishes there.

The week was punctuated by repeated observations that the event would not have been possible ten years ago, when the phrase land back wasn’t even in the vocabulary of the average architecture professor or student. That a symposium would provide the space for not one but two Palestinians to speak freely about Israeli apartheid would have been unimaginable just five years ago. Asked how she sneaks in political messages when working with large institutions worried about alienating their donor base, Palestinian designer Dima Srouji advised, “Ask for forgiveness, and not permission.” Her talk, which shed light on the use of archeology as a tool of empire, was a lesson in the courage integral to Palestinian resistance. Today, as Israel presses its indiscriminate bombing of Gaza, we watch mainstream media outlets justify war crimes by invoking dehumanizing Islamophobic stereotypes. The cowardice of those in power shows itself, too, as Israel’s openly genocidal rhetoric finds bipartisan support among all but a handful of sitting US politicians. It’s my hope that those reading this realize that now is not the time to cower in uncertainty, but to stand solidly with the Palestinian people of Gaza, who have been living in an open-air prison for the past sixteen years. —Sasha Plotnikova

OUT & ABOUT

East Side Story

Running the length of Manhattan’s west side, the Hudson River Greenway is familiar to most New Yorkers for both recreation and transit. The continuous thirteen-mile path is the “most heavily used bikeway in the United States” and has spurred development such as Little Island and Gansevoort Peninsula. The island’s east side is another story: A pathway along the East River, decades in the making, is still decades out from completion.

Even so, progress on that front is underway. The East Midtown Greenway runs alongside Sutton Place, the affluent micro-neighborhood where Midtown becomes Uptown, and where Woody Allen schmoozes Diane Keaton as Gershwin’s Someone to Watch Over Me begins to swell. Grid-wise, the enclave’s namesake avenue runs parallel to FDR Drive (over which its coveted co-ops and townhouses cantilever) from 53rd to 59th streets, stopping just short of the Queensboro Bridge (it continues north as York Avenue). By the end of this year or shortly thereafter, New Yorkers will be able to admire—and circumvent—the stately neighborhood from a seven-block, 2,000-foot “outboard” esplanade over the water.

The Urban Design Forum convened its tour of the East Midtown Greenway at Andrew Haswell Green Park, at the terminus of East 60th Street, atop a former waste transfer station that was converted to public space in the ’90s. Standing beneath the park’s signature Alice Aycock sculpture, NYC EDC’s Ankita Nalavade described how the EMG aims to close the loop of the Manhattan greenway, a project “undertaken by every mayor since 1993, to develop a continuous thirty-two-mile waterfront promenade around Manhattan.” The new esplanade, which is the northernmost of three segments of the larger East Midtown waterfront project, was visible in full from where we stood, at the southeast corner of the pavilion.

“EMG is unique because it’s set on the outboard of the shoreline,” Nalavade said, explaining that “in the early 2000s, State DOT decided to do some repair work on the FDR, and this was a detour meant for that.” The Outboard Detour Roadway was originally intended to be dismantled upon the completion of the repairs in 2006, but NYC Parks, subsequently undertook a feasibility study to convert it into a permanent pedestrian and bicycle way. Ultimately, the city kept the permits but not the caissons; the new structure is designed to withstand sea-level rise through 2100.

Stantec—represented on the tour by Gentry Lock, Amy Seek, and Donna Walcavage—won the public RFP in late 2017; construction started in fall of 2019 and is slated for completion this December, more or less on schedule despite a six-month pandemic pause. Unfortunately, it was only after we descended from the cantilevered pavilion to the construction site that foreman Rob informed us that policy required work boots; mere closed-toe shoes would not suffice. The non-compliant sneaker contingent, which included yours truly and a rather more renowned architecture critic, were relegated to an alternate tour, led by Lock, to view the esplanade from the pocket parks at the ends of East 53rd, 55th, 56th, and 57th streets (we skipped the one at the end of 58th Street, where that scene in Manhattan was filmed). Backtracking south through AHG Park, we strolled down under the Queensboro Bridge overpass to Sutton Place proper for an ad hoc neighborhood tour.

Sporting tan tennis shoes, the architecture critic shared more neighborhood lore, pointing out I.M. Pei’s former residence, as well as Andrew Bolton and Thom Browne’s manse. The power couple acquired the handsome Georgian number, designed in 1920 by Mott Schmidt for Anne Vanderbilt, in 2019, and were recently recognized by the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts for their “contribution to preserving the majesty of the Upper East Side through the careful renovation of their home.”

Per a New Yorker profile of Browne, the home features “an enormous lawn stretching down to the East River,” walled off from the Sutton Park at the end of 57th Street; from the terrace, writer Rachel Syme notes that “the water looked like a private lido.” We shoe-leather reporters got the view from the public park, from where the river appeared to be sandwiched between the new esplanade and Roosevelt Island. The greenway is forty feet wide per the specifications of the original DEC permit; as we could see from above, half of that is bike lane, the other is esplanade and planting; not visible is the substructure, composed of eighty-plus-foot-long tub girders, three bays wide for most of the greenway, some of which have been hollowed out to hold soil for the plantings—“a thousand cubic feet of soil per tree,” Lock said. To minimize visual impact, she credited architect Miguel Rosales with the elegant solution: angling the parapet walls such that they “cast light in a way that makes [the structure] look less bulky.”

In addition to pointing out the clusters of “art tiles” embedded at various points in the esplanade, Lock also shared the local legend of “Washington’s Rock,” an outcropping where the founding father reportedly stood during the Revolutionary War. We popped over to the end of East 55th Street to peer down at the water, where a partially submerged park bench and bicycle could be seen among the boulders. “Washington’s bench,” the critic quipped.

The tour ended at the foot of the bike/pedestrian bridge, designed by Rosales to DOT’s stringent specifications, which connects the EMG to mainland Manhattan at East 54th Street, over seven lanes of the traffic on the FDR. The sinuous ramp ascends from the awkward corner of South Sutton and East 54th to the bowstring truss spanning the highway. Nalavade and Lock noted that the next section of the greenway, currently in the design phase, will prove more challenging: the half-mile-or-so connection between the newly built portion and the so-called Waterside Pier at 41st Street comes with the major security headache of bypassing the UN Headquarters.

The timeline for that twelve-block stretch remains TBD, which means that EMG-goers will still have to pass by Sutton Place to access the outboard esplanade for years to come. “I’ve been working on [the East Side plan] since 1995,” Walcavage reminisced, even producing a brochure from that era. “So, I’m just letting you know that someday, it actually happens. You just need patience.” Call it waiting for the other shoe to drop. —Ray Hu

FAST & LOOSE

Brand Loyalty

Per its Instagram announcement, McNally-Jackson’s new Rockefeller Center location is an “effort to resurrect the lost tradition of grand, Midtown bookstores.” On the chilly afternoon I visited, the clean white walls, gold text, and ambient jazz combined with the occasional flash of a red sprinkler pipe to facilitate an elegant perusing experience. A few construction gaffes—gaps between wood panels, exposed nailheads, an awkwardly installed handrail—occasionally took me out of my reverie. But no matter: The shop’s best moment is the playhouse modeled after 30 Rockefeller Plaza in the children’s section. Hidden in the back, it’s a great spot to sit, flip through a self-help book, and contemplate why you, a nearly thirty-year-old, are sitting in a bookshop playhouse on a Saturday afternoon. —Zachary Torres

Y2Koolhaas

For all his Junkspace anti-consumerist rhetoric, Rem Koolhaas is phenomenally good at making shopping look fun. The apotheosis of this skill can be found in his Prada flagship in SoHo, built from 2001 to 2002. Twenty-two years later, this store is every bit as forward-thinking as it was then. Notably bifurcated by a half-slope–half-stair stage-cum–seating arrangement, the top floor of the store is pretty conventional retail. But the bottom floor, accessed by a cylindrical elevator, is something else entirely: a mix of big-checkered carpet, a wall that looks more like a metallic hill (a very Hans Hollein moment), and a bank vault–like row of Prada-green aisles. Koolhaas understood how changes in mood, material, texture, and light enhances the look of clothing, itself fundamentally architectural. It is astonishing how effectively Koolhaas’s approach of expanding, submerging, shrinking, and compressing space creates an exploratory consumer journey that feels intimate and lavish at the same time. The pastel colors and shiny textures of Koolhaas’s Prada’s Y2K aesthetic were cool and futuristic then. Outnumbered by boring white and concrete spaces for endless, mindless consumption, they’re no less cool and futuristic now. —Kate Wagner

Seeing the Forest

Cypresses, which traditionally line cemeteries in Mediterranean countries, serve as a reminder of life even amid death. Van Gogh likened them to an “Egyptian obelisk.” By the time he moved to an asylum in Saint-Rémy, he had started painting the trees as pairs of dark green figures in profile reaching toward a swirling baby blue sky. Their ominous, flame- like forms dominate the frames, looming over the yellow fields and flower beds. The technique would result in Starry Night and continue to occupy the artist in his mysterious final years. All this I learned on my visit to Van Gogh’s Cypresses, as peak-Met as we’re likely to see in our lifetime. Everyone else seemed to have the same thought. A QR code posted by the entrance estimated the wait to enter the exhibition at two and a half hours. I passed the time by—what else?—roaming the Impressionist collection, where visitors swarmed around Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat. —Jessica Jacolbe

DATELINE

The fortnight ahead…

Friday, 10/13

往復書簡 / Correspondence: The Many Lives of Arata Isozaki’s Shinjuku White House Opening Reception

6:00 p.m. ET | a83

Saturday, 10/14

Cooper Park Block Party

1:00 p.m. ET | Amant

Hannah Arendt’s New York City with Samantha Rose Hill

1:00 p.m. ET | Goethe-Institut New York

Monday, 10/15

Field Guide to Indoor Urbanism Book Launch with Phu Hoang, Rachely Rotem, & Enrique Walker

6:00 p.m. ET | Rizzoli Bookstore

Non-City Territory with Neil Brenner & Rosetta Elkin

6:30 p.m. ET | Pratt Institute School of Architecture

Open house lecture with Marc Tsurumaki & Andrés Jaque

6:30 p.m. ET | Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Tuesday, 10/17

Hans Noë in conversation with Lawrence Weschler, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, Alva Noë, and others

6:00 p.m. ET | MoMATH - National Museum of Mathematics

Wednesday, 10/18

Through the Lens: Honoring the Architectural Legacy of Paul Revere Williams with Carmen Beals, Daonne Huff, & Janna Ireland

6:00 p.m. ET | AIANY Center for Architecture

Current Work: Africatown, A Collaborative Approach with Claire Weisz, Jerome Haferd, Mario Gooden, Victor Body-Lawson, Renee Kemp-Rotan, & Farida Abu-Bakare

7:00 p.m. ET | The Architectural League of New York & Pratt Institute School of Architecture

Thursday, 10/19

A Dialogue on Education and Architectural Futures with Victor Body-Lawson, Kwesi Daniels, Rob Fleming, & Sharon E. Sutton

6:00 p.m. ET | AIANY Center for Architecture

Madame Architect Presents at the DVF Studio Headquarters with Amale Andraos

6:00 p.m. ET | Madame Architect

Old Buildings New Ideas: A Selective Architectural History of Additions, Adaptations, Reuse and Design Invention Book Talk with Françoise Astorg Bollack

6:30 p.m. ET | Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Monday, 10/23

Lina Bo Bardi: A Marvelous Entanglement with Isaac Julien, Esther da Costa Meyer, & Sunil Bald

6:30 p.m. ET | Yale University School of Architecture

Tuesday, 10/24

Times Square Remade: The Dynamics of Urban Change with Lynne Sagalyn

6:00 p.m. ET | The Skyscraper Museum

City-Making with Manuel Salgado

6:30 p.m. ET | Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Wednesday, 10/25

Field Guide to the Future with Carson Chan & Matt Wagstaffe

6:00 p.m. ET | Head Hi & New York Review of Architecture

Geospaces: Continuities Between Humans, Spaces, and the Earth with Alper Derinboğaz

6:00 p.m. PT |SCI-Arc

New York Review of Architecture reviews architecture in New York. Our editor is Samuel Medina, our deputy editor is Marianela D’Aprile, and our publisher is Nicolas Kemper.

To pitch us an article or ask us a question, write to us at: editor@nyra.nyc.

For their support, we would like to thank the Graham Foundation and our issue sponsors, Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects and Thomas Phifer.

To support our contributors and receive NYRA by post, subscribe here.