Published on October 20, 2020, in No. 16

This year’s combination of real crises with the possibility of radical change bears remarkable similarities to the fraught idealism of New York in the 1960s, making Mariana Mogilevich’s new book, The Invention of Public Space, a timely contribution. Examining a series of experimental urban design projects under Mayor John V. Lind-say’s administration (1966–73), Mogilevich shows how — both then and now — the importance of public space is clearer than ever, even as it remains unclear what it truly means for space to be public.

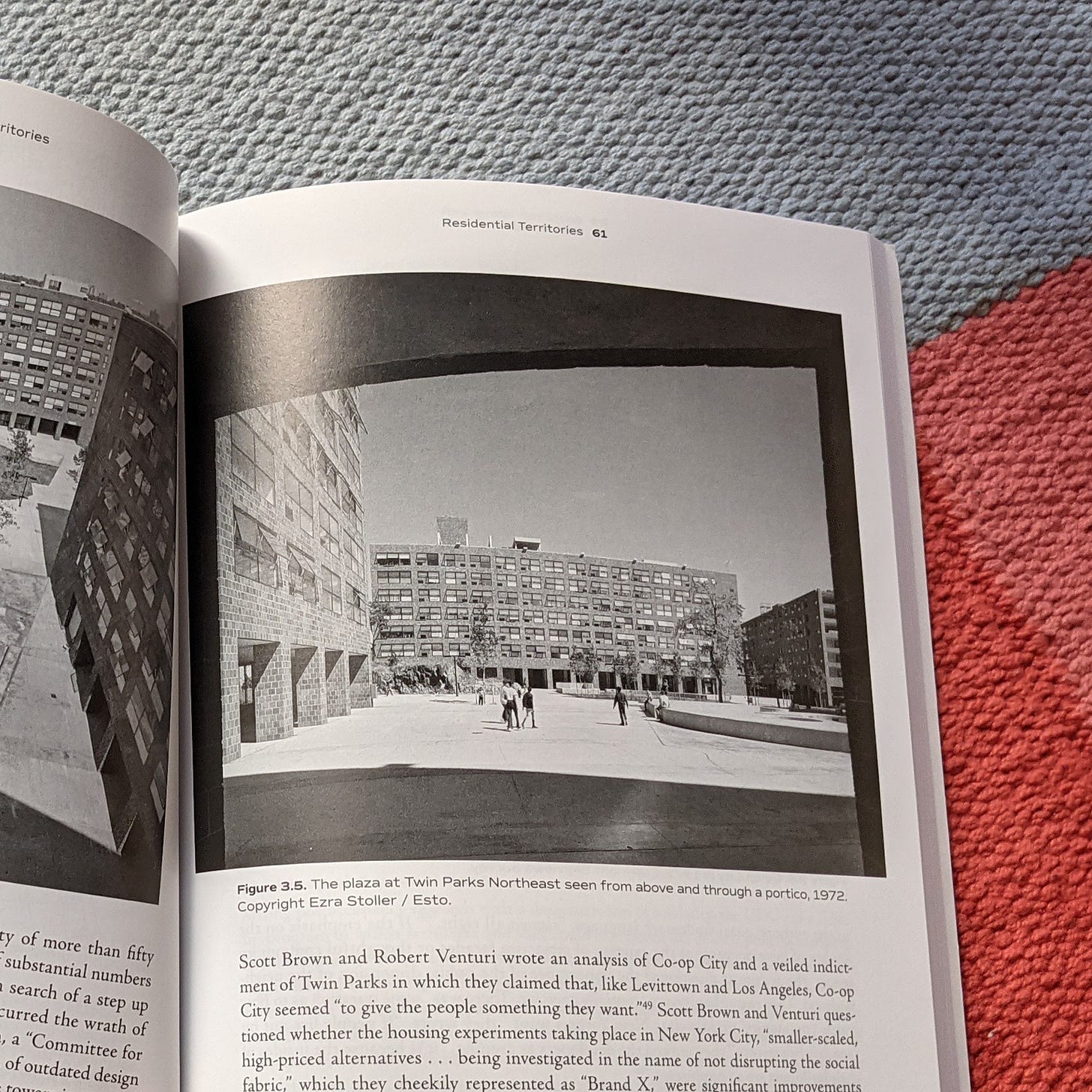

Architects use the word public rather casually, often as the antonym of private, when what we really mean are gradients of shared. This confusion played out with the 1966 Twin Parks Northeast residential development in the Bronx, a public housing project designed by Richard Meier and built by the Urban Development Corporation (UDC).

The plaza at Twin Parks was to be both a neighborhood nucleus and open to the city, a space to foster interpersonal and cross-cultural integration. Very quickly, however, it became contested ground for rival gangs. Residents called for fences and increased security. The space’s openness became a liability, prompting Kenneth Frampton, in a 1973 issue of Architectural Forum, to proclaim the project a utopian vision for a society that did not exist. Instead, architects turned to “defensible space,” a term that emerged from contemporaneous psychology studies on dynamics of territory and privacy. Marcus Garvey Village in Brooklyn, another UDC project designed by Frampton himself just a few years after Twin Parks, emphasized private entrances, private yards, and carports.

Twin Parks encapsulated the noble intentions of the architects, planners, and public officials of the Lindsay administration, chief among them the landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg. Inspired by psychological studies on play, his work on the Carver Houses Court in Harlem, designed with architect Simon Breines, and Riis Park Plaza on the Lower East Side did away with the look-but-don’t-touch landscapes so typical of New York City Housing Authority projects and rethought the shared spaces as three-dimensional grounds, dotted with programming and intended for full use by the residents.

Lindsay’s designers asked themselves what the public wanted, often attempting to integrate participatory design strategies into their process. The implicit expectation of participatory design — popular today as well — is that these processes, when they supplant traditional top-down design, will lead to more equitable spaces. By designing not only for the people but also with the people, Lindsay’s administration tried to create spaces to accommodate the city’s growing immigrant populations without demanding their assimilation.

For example, the city billed the multiplying tiny “vest pocket” parks as “neighborhood ventures” instead of “planner’s parks,” involving the people of those neighborhoods in their design. Some were popular, but maintenance and vandalism proved a problem. It became clear that the most essential aspect of these small parks projects was not their design and construction but the awakening of the commons, something that could be helped with programming but could not really be forced into existence. In the absence of funding, many vest pocket parks turned into walled-off communities not to reconstruct the commons but to retreat from it.

There are few physical traces left today from the urban experiments discussed in The Invention of Public Space. Even the popular and critically acclaimed Riis Park Plaza was demolished in 2000. Under the administration of Michael Bloomberg, New York City saw another public space renaissance, but its landmark projects, such as the High Line, the pedestrianization of Times Square, and Hudson Yards, were framed as value propositions instead of spaces explicitly designed for the self-actualization and socialization of a diverse population. The occupation of Zuccotti Park in 2011 and the killing of Eric Garner in 2014 by a police officer once again raised questions of who can access, control, and occupy public space.

Despite old and recent failures, the Lindsay administration’s aspiration for a diverse and inclusive democratic society realized in part through better public space remains in the collective subconscious. While Mogilevich stops short of advocating for a radical rethinking of collective ownership and democratic decision making, calling such proposals revolutionary even within the framework of public space, her final message is one of cautious optimism. Her last words are a plea to continue trying.

Mariana Mogilevich, The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York. University of Minnesota Press, 2020.