When the group Architectural Workers United announced in December that it was petitioning to create a union at SHoP Architects, an outpouring of support went out across the profession. A narrative quickly formed, one less concerned with SHoP than the need to empower architectural workers. Things felt inevitable.

They were not. There has not been an architecture union in nearly 80 years. Across the American workforce, union membership today (10.3 percent) is half of its 1983 level. Unless those who care get to work, there is no guarantee that today’s enthusiasm for unions will reverse that downward trend. So, we at NYRA asked our contributors to get to work and help our readers understand what is at stake. The articles assembled in #26 assume the form of reports, personal appeals, historical excursions, hypotheticals. As architectural workers at other firms weigh whether to proceed with their union drives, we hope this issue lends deeper context to their decisions. ⬤

Support the work, and subscribe to receive Issue #26, and we will put a copy in the mail for you.

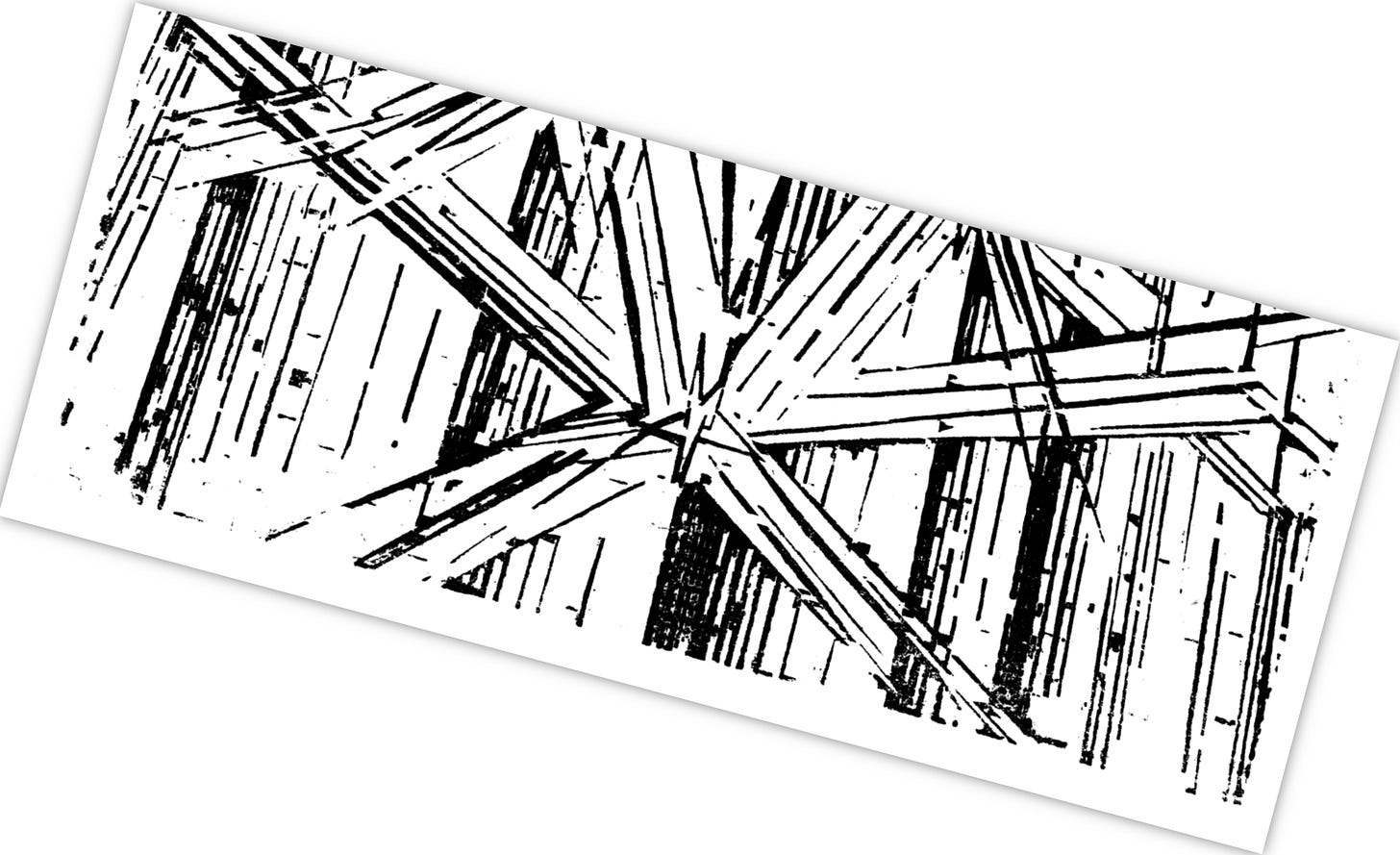

Like all of our issues, #26 is a limited edition Risograph print. Thanks goes to our graphic designer, Freer Studio, and Angela Sun for art. Included is a full page, 11x17 print of Lyonel Feininger’s 1919 woodcut Kathedrale. Read on below for some excerpts.

In the Issue…

DANIEL ROCHE: ORGANIZING SHoP

To be sure, the failed drive at SHoP is a major setback for the seedling labor movement within architecture. Nevertheless, since AWU went public, architects have openly debated the merits of unionizing the profession more than at any time in recent memory. Those sympathetic to the prospect might use this moment as an opportunity to take a step back, reflect, and learn from the current outcomes to plot the road ahead…

KATE WAGNER: DEAR ARCHITECT-WORKERS

Architecture is an inherently collective endeavor. This simple fact is routinely suppressed, has been suppressed, perhaps as long as architecture has existed. The solitary genius overshadows the hundreds, if not thousands, of people working together to execute ideas into something real. Within this collective lies the lifeblood of any firm, for which the sole architect is but a figurehead, and sometimes not even that…

NICOLAS KEMPER: ANTITRUST AND ARCHITECTURE (COORDINATION NOT DOMINATION)

The drive to unionize architects looks like a contest between management and labor. This characterization, however, would be misleading. While a union may focus on the relationship between the leaders of firms and their employees, the costs of accommodating their demands will ultimately be shouldered by clients. It would be logical, then, that just as workers are organizing to bargain with their bosses, bosses should coordinate to bargain with their clients. Logical, but illegal…

ANTONIO PACHECO: PERNICIOUS EFFECTS

Professional architects have a thin track record of shaping federal legislation favorable to their interests. The Tarsney Act of 1893 is the rare exception, marking the first time practitioners organized to gain an economic and cultural foothold. But like the Sherman Antitrust Act of three years earlier, the measure ultimately accomplished the opposite…

A CONVERSATION WITH RIO MORALES, ELISA ITURBE, and JESS MYERS: UNIONS AND CLIMATE ACTION

In architecture our workplaces can be very small, and we can have close relationships with the people who manage a project that we work for. The union is not necessarily about bringing in constant antagonism, but recognizing that we should all actually consent to the conditions of work. You’re bringing back this notion of consent, and that is important at so many scales—at the scale of the life of an individual, the life of a worker—but also, it’s what’s at stake right now. So much of the built environment is produced without our consent…

VERONICA MALDONADO: THE SPACE BETWEEN

Architecture, both process and product, influenced Isamu Noguchi’s sculptural practice. But the compulsion to show prevents Useless Architecture from reaching this goal…

PHILLIP DENNY: CATHEDRAL OF LABOR

Amid the chaos of the postwar era, German artists and architects forged new associations free from the imperial academies and hidebound institutions of the former Wilhelmine system. The Arbeitsrat für Kunst (“Workers’ Council for Art”) was arguably the most influential of the organizations to appear after the war. Established in Berlin in 1918 by architects Bruno Taut and Walter Gropius alongside artist César Klein and critic Adolf Behne, the Arbeitsrat, like other postwar groups throughout Germany, modeled itself after Russian revolutionary “workers’ soviets,” or councils…

To support our contributors and receive #26 by post, subscribe here.

Props to Angela Sun for the art and Erik Freer for graphic design.

Four desk editors run NYRA: Alex Klimoski, Phillip Denny, Carolyn Bailey & Nicolas Kemper (who also serves as the publisher).

To pitch us an article or ask us a question, write to us at: editor@nyra.nyc.

For their support, we would like to thank the Graham Foundation and our issue sponsors, Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, Thomas Phifer, and Stickbulb.

To support our contributors and receive the Review by post, subscribe here.